CHI PORTA I PANTALONI? DECLINAZIONI TRA MASCHILE E FEMMINILE

Natura docet. E’ il leone, e non la leonessa, ad avere una criniera sontuosa. E’ il pavone maschio a sfoggiare una ruota dalla bellezza strabiliante. Si è già detto che “la vanità è uomo”. Ma lo sfaccettato rapporto tra il vestire al maschile e quello al femminile va ben oltre questa considerazione. Si tratta di una relazione da sempre bidirezionale, scandita da interscambi, commistioni, condivisioni di fogge, tipologie e materiali. E’ più facile cogliere ciò che la donna, a partire dall’inizio del ventesimo secolo ha “rubato” all’uomo in fatto di abbigliamento. Nel nome sacrosanto dell’uguaglianza e dell’equiparazione. I pantaloni sono l’elemento più scontato, non certo l’unico.

Ad essi si affiancano il completo da lavoro – il tailleur in tessuti e fantasie maschili – magari ingentilito. E ancora, la camicia dal taglio severo, che i signori completano con la cravatta e le signore sbottonano un poco ed ingentiliscono con un foulard o un gioiello. L’apoteosi probabilmente si raggiunge grazie a Christian Dior. Mentre i grandi d’Europa ricostruivano il continente dopo le devastazioni della Seconda Guerra Mondiale, lui ricostruiva il glamour dopo gli anni delle privazioni e lo consegnava al presente.

Ma lo ha fatto ricorrendo, appunto, anche a textures e disegnature tradizionalmente da uomo – lane “secche” gessate, a Principe di Galles, a pied de poule – con cui ha realizzato persino abiti da sera incredibilmente sontuosi. Ed indiscutibilmente femminili, donanti, sensuali. Più sottile, ma non meno intrigante, è la lettura di ciò che è accaduto in direzione opposta. Si può capire che cosa l’uomo ha fatto proprio attingendo al vestire femminile? Sicuramente sì. Avendo però presente che la barriera tra i due guardaroba è un dato relativamente recente. Risale all’inizio del diciannovesimo secolo, con l’affermazione del ceto borghese ed una codificazione dei canoni dello stile tanto rigida quanto la morale pubblica ufficialmente stabilita – non sempre privatamente praticata – dalla nuova classe dominante.

Sino ad allora abbigliamento maschile e femminile avevano viaggiano in parallelo, se non in sovrapposizione. Dall’antichità a tutto il Medio Evo, donne e uomini si coprivano con tuniche e mantelli. Le tuniche potevano avere o non avere le maniche, potevano essere fermate in vita da una cintura, potevano essere più o meno lunghe. In sintesi: cambiavano i dettagli, ma non certo la foggia di base. Più tardi, dal Rinascimento all’era napoleonica, le tipologie un po’ si diversificano. Compaiono i pantaloni, a metà coscia prima, al ginocchio poi. E sono gli uomini a portarli.

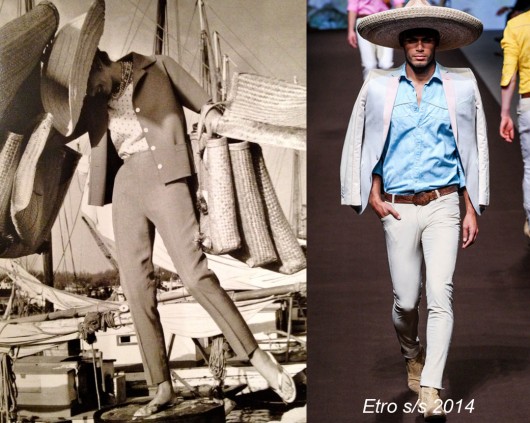

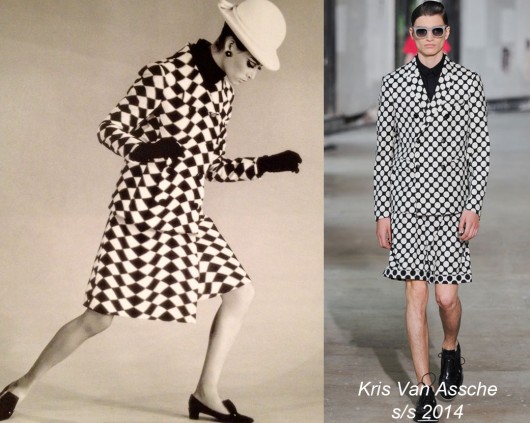

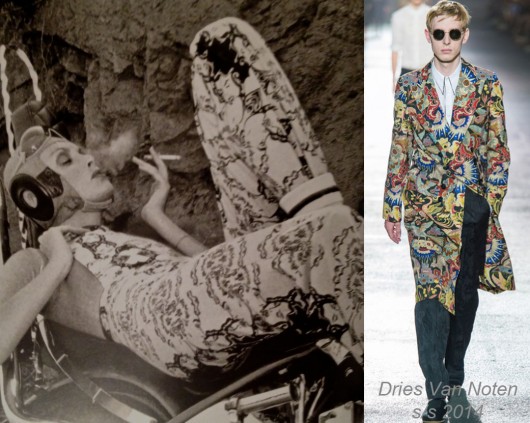

Ma al di là di ciò, qualcuno può stabilire se fossero più preziosi i ricami, le applicazioni di pietre preziose, gli intarsi che arricchivano gli abiti di Enrico VIII o quelli di Elisabetta la Grande? Quelli di Luigi XVI o quelli di Madame du Barry? Senza parlare delle acconciature, della cascate di pizzi, nastri, volants, ruches usati in profusione al maschile come al femminile. Ora abbigliamento maschile e femminile si sono reciprocamente “ritrovati”. L’uomo riscopre l’uso del colore per esempio, dopo oltre un secolo di grigio, marrone, blu, nero… Non ha più paura di mostrare il corpo e, con esso, la propria sensualità, anche nel vestire formale, strizzando ben bene il cappotto o il trench, come fa la donna.

Scegliendo giacche con tagli, revers ed abbottonature che “segnano” il torso nei punti-chiave, vita e spalle in primo luogo. Indossando maglie fluide che non sono più dei semplici “sotto giacca”. Del resto, qualcuno oggi trova strano che un uomo porti un twin set? Osando con gli accessori, dalle cinture ai cappelli. Non rinunciando più a ricami e lavorazioni non solo sulle camicie, ma anche sui capi-spalla. L’uomo continua a portare i pantaloni. Questo è certo. Ma sa benissimo che da quasi cento anni li porta anche la donna. Giorgio Re

Dettagli di foto di Norman Parkinson ricavate dal volume “Parkinson Photographs 1935-1990” di Martin Harrison.

Who wears trousers? Variations between masculine and feminine. Natura docet. The lion, not the lioness, has a magnificent mane. The male peacock flaunts his astonishing tail. It has been already said that “vanity is man”. But the multifaceted connection between menswear and womenswear goes beyond this consideration. It’s always been a bidirectional connection, marked by interchanges, mixtures, sharing of shapes, varieties and fabrics. It’s easier to understand what women, from the beginning of the 20th century, have stolen from menswear. In the sacred name of equality and levelling. Trousers are the most expected element, but it’s not the only one. It’s proper to mention the working suit – the tailleur in masculine fabrics and patterns – maybe refined. And, the severely tailored shirt, that gentlemen complete with a tie and ladies unbutton a bit and refine with a scarf or a jewel. The apotheosis has been reached thanks to Christian Dior. While the great powers in europe rebuilt the continent after the Second World War, he rebuilt glamour after years of deprivations, and consigned it to the present. But he did it using, indeed, also tipically masculine textures and paterns – pinstriped, glencheck, hound’s tooth “dry” wool – even for incredibly sumptuous evening gowns. And they were unquestionably feminine, becoming, sexy. Subtler, but not less intriguing, is the interpretation of what happened in the opposite direction. Can we understand what men took from womenswear? Definitely yes. But we have to keep in mind that the division between the two kinds of style is pretty recent. It dates back to the beginning of the 19th century, with the bourgeoisie’s achievement and a coding of style rules as strict as the public morality – not always practised in private – officially established by the new leading class. Till then menswear and womenswear were parallel, sometimes overlapping. From the ancient times to the Middle Ages, men and women wore tunics and capes. Tunics could have been with or without sleeves, tight by belts, more or less long. To sum up: details changed, but shapes remained the same. Then, from Renaissance to napoleonic age, they diversified a little. The trousers appear, and they were first short, then knee-lenght. And they were worn by men. But beyond this, can someone decide what embroideries, gemstones’ ornaments, trims, between the Henry VIII’s and Elisabeth the Great’s were more precious? The Louis XVI’s or Madame du Barry’s? Not to mention the coiffures, a profusion of lace, ribbons, frills, ruches both for men and women. Now menswear and womenswear “meet again”. For example man rediscovers colours, after a century of grey, brown, blue, black…he isn’t scared to show his body and his sensuality anymore, even in formal clothing, tightening the coat or trench, as the woman does. Choosing jackets with cuts, lapels and buttons that “mark” the chest in the key-points, first of all waist and shoulders. Wearing fluid sweaters that can’t be called simply “under-jacket”. On the other hand, does it seem strange to anyone if a man wears a twin-set? Daring with accessories, from belts to hats. Not giving up emboideries and decorations, not only on shirts, but also on outerwear. Man keeps on wearing trousers. This is sure. But he knows well that, since around 100 years ago, they’ve been worn by woman too. Giorgio Re