TRE, NUMERO PERFETTO. PER L’APLOMB MASCHILE.

“Gilet” in francese e in italiano – panciotto in verità -; “waistcoat” in inglese, “Weste” in tedesco, “chaleco” in spagnolo. E da qui si parte. O meglio, dalla Spagna dominata dagli Arabi per secoli. Mediato dal turco “yalec”, il termine approda nella parte meridionale del nostro continente, per designare un capo relativamente corto e senza maniche, che “los moros” indossano sopra la tradizionale djellaba, la tunica ampia e lunga che costituisce ancor oggi, pur con nomi differenti, la base del’abbigliamento tradizionale maschile dal Maghreb all’India. Certo, il gilet contemporaneo ha anche i suoi ascendenti occidentali. Il farsetto – o giubba – medioevale e rinascimentale, indossato in particolare dagli uomini di giovane età e stretto al busto dai nastri posizionati sulla schiena: ricamato, intarsiato, abbellito in mille modi. Il capo ideale per esaltare un fisico ben fatto e in cui pavoneggiarsi. Nell’evoluzione del vestire al maschile, il gilet perde il suo ruolo “autonomo”, ma entra a far parte, accompagnandosi a giacca e pantaloni, della “trinità” che costituisce il caposaldo dello stile formale da uomo, il completo a tre pezzi. Ciò accade quasi un secolo prima dalla istituzionalizzazione dell’abito borghese. Ancora in epoca di Ancien Régime. Tanto il ceto aristocratico come la classe borghese usano vestire la giacca a marsina che si allarga verso il fondo, i pantaloni al ginocchio ed il gilet con le falde anteriori un po’ più lunghe della parte posteriore che si ferma in vita. A seconda del livello sociale mutano tessuti, colori, dettagli. Non solo per ragioni di possibilità economiche. Soprattutto per motivi di rappresentanza, per visualizzare uno status ben preciso.

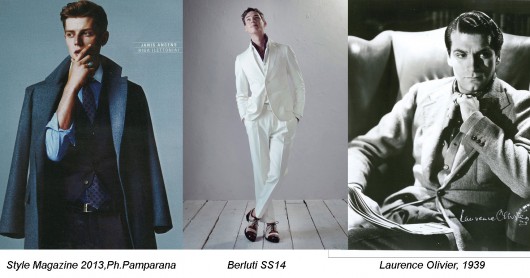

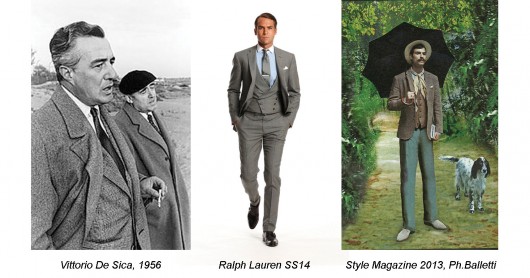

Per la “bourgeoisie” in corsa verso il potere, soprattutto nei Paesi in cui domina l’etica luterana o calvinista, è quasi doveroso indossare giacca, pantalone e gilet del medesimo colore, spesso scuro e severo, di materiali solidi e resistenti, a testimoniare la validità di certezze morali attraverso sobrietà e misura. All’opposto, l’aristocrazia si veste di tessuti preziosi, rari, costosi. Si pone al di fuori della norma e vive al di sopra delle righe, in un gioco alla costante ricerca della stravaganza, del “dernier cri”. Ed il gilet concede campo libero ad un florilegio di decorazioni, stampe, ricami, applicazioni. E’ la fiera delle vanità trasformata in capo d’abbigliamento. Congresso di Vienna e rivoluzione industriale ridefiniscono gli equilibri. Il completo a tre pezzi diventa LA norma del vestire formale. Così come diventa norma la pacatezza. I pantaloni arrivano al suolo, la giacca, decennio dopo decennio, cambia foggia ma non così tanto, il gilet resta, di norma nello stesso colore e materiale. Non sempre: dandy e bohémiens, seppur nel rispetto della regola della “trinità” vestimentale, concentrano nel gilet tutti i loro sforzi per “épater le bourgeois”. Così si procede sino ad oggi. Con qualche decennio, i Sessanta in particolare, che vede i tre pezzi ridursi quasi sempre a due, in un processo di sveltimento ulteriore del vestire e di assottigliamento della silhouette maschile. Con qualche ritorno di fiamma: i broker rampanti alla Michael Douglas in versione Wall Street optano per completi super gessati, sopra camicie iper-rigate, abbinate a gilet “too much” o a bretelle in bella vista larghe sino a quattro dita. Fuochi di paglia… Nella moda contemporanea è abbastanza raro che certe esasperazioni abbiano spazio o mercato. Si vedono semmai in passerella, Non certo nelle vetrine. Del resto tre è anche il numero dell’armonia. Giorgio Re

“Gilet” in french and italian – “panciotto” on the square -; “waistcoat” in english, “Weste” in german, “chaleco” in spanish. And from here we start. Or better, from Spain dominated by Arabs for centuries. From the Turkish “yalec”, the word came in the southern part of our continent, to define a quite short and sleeveless garment, worn by “los moros” over the traditional djellaba, the long and wide tunic that represents still today, although with different names, the basis of traditional menswear from Maghreb to India. Of course, the modern waistcoat has its ancestors in Western world too. The medieval and renaissance doublet – or jerkin-, especially worn by young men and tied at the bust with ribbons on the back: embroidered, embellished, adorned in a thousand ways. The perfect garment to accent a well-built body, in which strutting about. In menswear evolution, the waistcoat lose its “independent” role, taking part, with jacket and trousers, in the “trinity” that represents the cornerstone of the formal style, the three-piece suit. It happens almost a century before the institutionalization of the conventional suit. Still in Ancien Régime era. Both the aristocracy and the middle-class use to wear the tailcoat widen at the bottom, the knee-lenght trousers and the waistcoat with the anterior part a bit longer than the back. Depending on the social class, fabrics, colours and details change. Not only for economical reasons. Mainly for representative reasons, to focus a precise status. For the “bourgeoisie” in rise to power, especially in Countries in which prevails the lutheran or calvinist ethics, it’s proper to wear jacket, trousers and waistcoat in the same colour, often dark and severe, made of heavy and resistant fabric, to highlight the efficiency of moral certainties through sobriety and moderation. On the contrary, aristocracy wears precious, rare, expensive fabrics. It put itself in high standards and lives above the line, in a constant research of extravagance, the “dernier cri”. And the waistcoat leaves space to a triumph of embellishments, prints, embroideries, trimmings. It’s a vanity fair transformed in a piece of clothing. The Wien Congress and the industrial revolution redefine the balances. The three-piece suit becomes THE rule of formal clothing. In the same way the placidity rules. The trousers are long, the jacket, decade after decade, changes its shape but not so much, the waistcoat keeps the same colours and fabric. But not always: dandy and bohemiens, even if in the respect of the “trinity”, concentrate in waistcoat all their efforts to “épater le bourgeois”. And so on, till today. With some decades, the Sixties in particular, when the suit becomes quite always a two-piece, in a process of further acceleration of dressing and slimming of male silhouette. With some back in love: the ambitious brokers (think about Michael Douglas in Wall Street) opt for hyper-pinstriped suits, over hyper-striped shirts, matched with “too much” waistcoats and four-fingers wide suspenders. Flashes in the pan…in contemporary fashion those exaggerations rarely have field or trade. Maybe we see them on catwalks, surely not in windows. Furthermore, three is the number of harmony. Giorgio Re