PAINTED FASHION

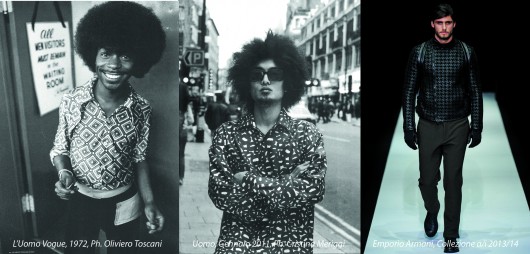

Da sempre l’abito è stato considerato una sorta di tela da pittore, come il corpo umano. Nelle culture sbrigativamente definite primitive, pitture e tatuaggi sulla pelle raccontano lo status sociale dell’individuo o la sua abilità nella lotta e nella caccia, secondo un repertorio sterminato di valenze simboliche. Dal corpo all’abito: tessuto, pelle e maglia, rappresentano una tabula rasa da arricchire di disegni, colori, lavorazioni – intarsi, jacquard, trafori – tra assonanze e contrasti cromatici. Non fanno pensare ad un quadro le marsine del “giovin signore” settecentesco o i gilet del dandy vittoriano, ricamati a motivi floreali o decorati da figure di animali? La diffusione del cotone ed il progresso delle tecniche di stampa, a cavallo della rivoluzione industriale, accelerano la tendenza. Per duecento anni la mussola a piccoli disegni, relativamente a buon mercato, fornisce camicie maschili, già prodotte in serie, alle classi lavoratrici. Fantasie più severe e più sofisticate – righe, check, pied de poule, Principe di Galles, tartan –disegnano l’uniforme dell’uomo borghese. Senza dimenticare che “la pittura dell’abito” ha costantemente guardato alla pittura in sé. La moda “ruba” tutte le correnti dell’inizio del ventesimo secolo: Dadaismo, Cubismo, Costruttivismo, Surrealismo, Astrattismo, Futurismo. Se non ai singoli maestri: Mondrian, Vasarely, Mirò, Dalì, Warhol. In questo interscambio la creatività applicata alla moda tiene sempre in considerazione le “altre” culture, come punto di riferimento sistematico nella scelta di motivi e fantasie. Recuperando tra l’altro elementi figurativi primordiali: body art, tattoo, stampe batik e lavorazioni yakut, disegni – elementari, ma coloratissimi e di forte impatto – delle stoffe prodotte dalle tribù africane o nativo-americane, dell’Oceania, delle Ande. Questo fenomeno nasce poco più di quaranta anni fa, sostanzialmente in concomitanza con il recupero da parte degli Afro-Americani della consapevolezza delle loro radici. E da allora rappresenta un leit motiv della moda contemporanea. Si parte dalle camicie a macro-stampe ipercolorate dei primi Settanta per arrivare ai grafismi decisi ed astratti di Prada di inizio millennio. Ed ora, al blouson in nappa di Emporio Armani, in cui intarsi incredibili riescono a sommare tra loro motivi pied de coq e suggestioni etnico-tribali, vagamente guerriere. Giorgio Re

Clothes have been always considered as a painter’s canvas, as well as the human body.

In, offhandedly defined, primitive cultures, drawings and tattoos on skin narrate the person’s social status or his skill in fighting and hunting, on the basis of an endless variety of symbolic values. From the body to the garment: fabric, leather and knitting represent a blank slate to enrich with prints, colours, embellishments – marquetries, jacquard, openworks – between assonances and chromatic contrasts. Doesn’t the tail coat of the eighteenth-century gentleman or the victorian dandy’s waistcoats, embroidered with floral or animal motifs, make you think about a painting? The spread of cotton and the print techniques’ improvement, during the industrial revolution, hastened the trend. For two hundred years the micro-printed muslin, moderately cheap, supplied mass-produced male shirts to the working classes. More austere and sophisticated patterns – stripes, checks, hound’s tooth, glenchecks, tartan – became the middle-class uniform. Don’t forget that the “clothes’ painting” has been constantly inspired by Painting itself. Fashion “steals” all the art movements of the early20th Century: Dadaism, Cubism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Abstract art, Futurism. Or the works of masters: Mondrian, Vasarely, Mirò, Dalì, Warhol. In this interchange, creativity applied to fashion always consider “other” cultures as a systematic reference frame in motifs’ and patterns’ choice. Recovering, besides, primordial figurative elements: body art, tattoo, batik prints and yakut embellishments, drawings – simple, but colorful and with strong effect – of the fabric made by tribes from Africa, Oceania, Andes. This phenomenon was born about fourty years ago, essentially in conjunction with the recovery by the Afro-Americans of the awareness of their roots. From then on it has represented a leitmotif of contemporary fashion. Starting from hypercolorful macro-printed shirts of the early 70s to strong and abstract graphic prints by Prada of the beginning of this millennium. And now, to the leather jacket by Emporio Armani, wherein incredible marquetries create hound’s tooth motifs and ethnic-tribal, vaguely warriorlike, suggestions. Giorgio Re